Let’s Talk!

We’re here to help you with any questions you may have. Please don’t hesitate to reach out to us.

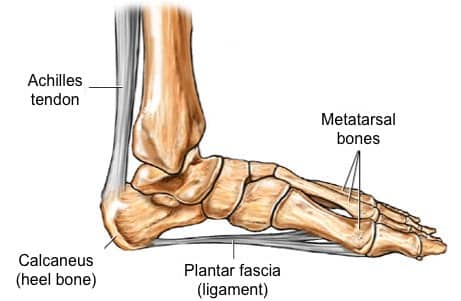

Plantar fasciitis (also referred to as subcalcaneal pain, painful heel syndrome, calcaneodynia, heel spur syndrome, runner’s heel, and calcaneal periostitis) is the most frequently reported cause of heel pain. It involves pain and inflammation of a thick band of tissue, called the plantar fascia that runs across the bottom of your foot and connects your heel bone to your toes. In untreated or poorly managed cases, Plantar Fasciitis can dramatically impact physical mobility and overall quality of life.

Unfortunately, the exact cause or pathophysiology of Plantar Fasciitis is not known in about 85% cases; but it is believed that the condition is mostly multifactorial in origin i.e. a wide variety of mechanical, anatomical and environmental factors plays a vital role in its pathogenesis(5). Although Plantar Fasciitis is more common in dynamic individuals; the risk is significantly high in general population as well, especially middle-aged women with a sedentary lifestyle(6).

The structural integrity of foot is reinforced by thick bands of connective tissues that form plantar arches and fascia in order to enhance biomechanical alignment and optimal physiological functioning of the foot to promote effortless walking and weight bearing.

The Plantar Fascia consists of thick connective tissue which supports the Medial Longitudinal Arch on the sole (plantar side) of the foot. It runs from the medial tuberosity of the calcaneus (the inside of the heel bone) forward to the heads of the metatarsal bones. The plantar fascia is made up of predominantly longitudinally oriented collagen fibers and it looks like a white, flattened or ribbon-like tendinous expansion. it includes a thick central component and thinner medial and lateral components. Contributes to the support of the foot by absorbing as much as 14% of the total load of the foot.

There are significant risk factors that plays a vital role in the initiation and progression of plantar fasciitis:

Plantar fasciitis is the most frequently reported and disabling disorder of the foot, but very little is known about the exact cause. It is thought that ongoing injury which causes microtearing and persistent inflammation of the plantar fascia at its origin (i.e. calcaneus) resulting in the degeneration of the connective tissue band(9).

It has been suggested that plantar fasciitis represents a form of tennis elbow at the heel with the condition being caused by repetitive microtrauma at the point of insertion of the plantar fascia.

Whenever the heel is in contact with the ground (such as during walking), the foot automatically pronates due to inward movement of tibia. This leads to stretching of the plantar fascia and the pressure generated due to this stretching flattens the plantar arches. In simple words, this arrangement acts like shock absorbers in accommodating the pressure and stress from walking. In the presence of certain contributing risk factors (listed above such as obesity, improper foot gear etc.), the fibers of plantar fascia undergo excessive stretching and micro tearing(1)(10). Most commonly, the micro-tearing begins at the site of origin of Plantar Fasciitis – the medial prominence or tuberosity of the calcaneus. If left untreated, the process of tearing causes degeneration of fascial fibers and associated connective tissue elements.

Plantar fasciitis is usually a self-resolving condition especially when treated early with conservative treatments. However, once the degeneration and persistent inflammatory reaction sets in, it is usually a downhill course. The plantar fasciitis usually presents with persistent pain in the infero-medial aspect of the heel. The pathophysiology of pain is complex and is often described as a multitude of various pathological processes such as loss of normal elasticity of fascial fibers, abnormal changes in the vascularity due to fibrosis, thickening of the plantar fascia and inflammatory destruction. In the absence of any meaningful interventions to control the process or minimize the ongoing damage (stretching, orthotics, shoes modification, night splinting etc.), most patients develop severe morbidity and disability.

Plantar fasciitis is usually a self-resolving condition especially when treated early with conservative treatments. However, once the degeneration and persistent inflammatory reaction sets in, it is usually a downhill course. The plantar fasciitis usually presents with persistent pain in the infero-medial aspect of the heel. The pathophysiology of pain is complex and is often described as a multitude of various pathological processes such as loss of normal elasticity of fascial fibers, abnormal changes in the vascularity due to fibrosis, thickening of the plantar fascia and inflammatory destruction. In the absence of any meaningful interventions to control the process or minimize the ongoing damage (stretching, orthotics, shoes modification, night splinting etc.), most patients develop severe morbidity and disability.

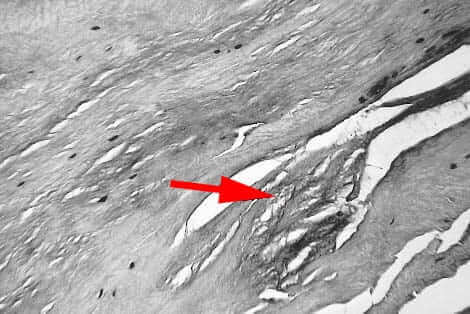

The histological changes in plantar fasciitis vary according to the age of the patient and duration of symptoms. The Plantar Fascia fibers are thicker in younger people and as an individual ages, the concentration and continuation of fibers decrease(12).

Most investigators prefer the term fasciosis to define the degenerative pathological processes in the Plantar Fasciitis instead of fasciitis to indicate that plantar fibrosis is a degenerative process without inflammation. Histological examination of plantar fasciitis reveals myxoid degeneration of the fascia(13) associated with fragmentation. Severe and chronic cases of plantar fasciitis show typical granulomatous changes besides localized fibrosis and scarring(14). Other histological findings may include collagen necrosis, angiofibroblastic hyperplasia, chondroid metaplasia and matrix calcification, scar deposition etc.)

In view of such findings, it is surprising that so many patients seem to respond to local steroid injections and oral anti-inflammatory drugs. However, this paradox is hardly unique to plantar fasciitis. Both lateral and medial epicondylitis respond to similar treatments in spite of the inability of modern histologists to find inflammatory changes at the site of tenderness. It must also be remembered that histology is not obtained on all patients with heel pain and the absence of inflammation in the subgroup (less than 1%) that comes to surgery may not be an accurate representation of plantar fasciitis patients as a whole.

For appointments and enquires:

Phone: (774) 421-9144

This information is for educational purposes only and is NOT intended to replace the care or advice given by your physician. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider before starting any new treatment or with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. For more information see our Medical Disclaimer.

– Privacy Policy – Terms of Use –

Copyright 2023 © The Center for Morton’s Neuroma. All Rights Reserved.

We’re here to help you with any questions you may have. Please don’t hesitate to reach out to us.

The Center for Morton's Neuroma